By Fred Novomestky, Ph.D.

There has been considerable interest, discussion and debate on investing in gold since the recessionary period that started in 2008. Regular television viewers have been barraged with advertisements saying that it has never been a better time to move a portion or all of our assets into gold investments. The current downgrade of U.S. debt by Standard & Poors has fueled aggressive trading in the gold spot and futures markets.

The article by John Dizzard in the May 9, 2011 edition of the Financial Times Monthly Review on the Fund Management Industry has an attention grabbing title, “Reasons not to fondle your gold”. He carefully reminds the reader that gold is “real” money. Real money, un-invested in any opportunity, does not earn any return. We are talking here about gold as precious metal or hard currency. Warren Buffet was quoted as saying that if you owned all the gold in the world it would not earn anything for you. On the other hand, if you owned all the farmland in the U.S. and several large oil companies you could earn something, the “stuff”.

John Dizzard references a study that was performed by Larry Summers and Robert Barksy, Gibson’s Paradox and the Gold Standard, in 1985 [see the article at http://www.gata.org/files/gibson.pdf ]. The authors found a “Strong co-movement between the inverse relative price of gold and the real interest rates ….”. That is, if real interest rates on bonds or equity yields are high, holders of money have more incentive to use their cash to buy assets.

In a multi-year investment strategy, the flat-currency price of gold will by flat or decline when real returns on assets are high. Conversely, when real returns have been low or stagnant, then gold has been strong.

The author closes by saying that in the current economic environment gold is a useful capital preserver. Over decades staying in cash rather than earning assets is fruitless.

We are going to do a simple test of the research by Summers and Barksy using the quarterly real returns for the five equity and fixed income asset classes that were used in the blog on Purchasing Power and Commodities [provide a link]. We consider four (4) ten year time periods: 1971 to 1980, 1981 to 1990, 1991 to 2000, and 2001 to 2010.

The gold prices used for the empirical analysis were downloaded from the web site of the World Gold Council, http://www.gold.org. The gold price used on this site is the London PM fix. This price is quoted in US dollars. Where the gold price is presented in currencies other than the US dollar, it is converted into the local currency unit using the foreign exchange rate closing price on the same day...

Economists and statisticians have used a measure called correlation to quantify the statistical dependency between pairs of financial variables. The correlation measure takes on values between -1 and +1. Our financial variables are quarterly growth rates in the spot price of gold and the real returns of U.S. stocks and bonds. When the correlation between two variables is close to +1, we say that an increase in one variable is most often accompanied by an increase in the other variable. At the other extreme, when the correlation is close to -1, then an increase in one variable is most likely accompanied by a decrease in the other variable.

Tables 1 to 4 summarize the estimated correlations between gold and each of the financial asset returns over the four time periods. The column of interest is the first column and, specifically, the values below the first row which are highlighted in bold. These represent the correlation between gold growth rates and the real returns of the assets. The theory as set forth by Summer and Barksy would suggest negative correlations with stock real returns and positive correlation with bond returns (similar to the negative correlation with real interest rates).

There are several observations that are noteworthy. The first is that, in general, there is a slight negative correlation between gold returns and real returns of stocks but only in three of four ten year periods. The second observation is the general positive correlation between gold returns and bond real returns but not in all ten year periods. It is also interesting to note that the magnitude of the correlations between gold and financial assets is small. The statistician would run a test to determine if these correlations are really different from zero. The report would indicate that they are not really different from zero as one would expect in the correlation between risky assets and a risk-less investment.

The long term investor can benefit from a strategic exposure to gold in their portfolio just as cash is a powerful diversifying instrument. Then again, gold is just real money.

Click to Enlarge

Sponsored by: EMA Softech

Sponsored by EMA Softech - Providing investment analysis software and consulting services to leading financial institutions and investment advisors worldwide since 1987

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

Purchasing Power and Commodities

By Fred Novomestky, Ph.D.

It is difficult to think beyond the crisis we have been facing as a deal is made in Congress to increase the debt ceiling. Conflicting economists predict either a recession worse than the one in 2008, or a continuation of sluggish economic growth. The baby boomers are faced with the problem of how to safeguard the assets they have, and somehow protect themselves from running out of money before their time.

This blog takes a look at how asset classes have fared over the forty year period 1971 to 2010 by using partial moments to quantify the likelihood that the purchasing power of these asset classes is protected and to what extent. It is helpful to see how annual inflation has changed over this time. Figures 1 to 4 show what happened. OPEC I and OPEC II occurred in 1974 and 1980. Investors at that time enjoyed double digit interest rates in their CD’s but also had to deal with double digit inflation. Since then, we have been enjoying inflation rates between 3% and 4%. In 2008, the inflation rate was just below zero.

Economists measure purchasing power by calculating the real return of investments. While we use the textbook formula for computing real returns, they are often approximated by subtracting the inflation rate for a given time period from the nominal or total returns of an investment. To protect purchasing power, the investor wants real returns that are greater than zero as often as possible (ideally all the time). If we apply the partial moment methodology, then the target return for real returns should be zero.

Table 1 illustrates how to evaluate the lower and upper partial moments for the real returns of commodities. They are represented by the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index using the quarterly returns and inflation rates over the time period 2006 to 2010. The downside loss was 6.0891% while the upside reward was 5.6120%. Con Keating and William Shadwick of The Finance Development Centre in London, developed a useful risk adjusted measure to rank investments in a partial moment context. They call it the “omega measure”, and it is defined as the ratio of upside reward (upper partial moment of order 1) to downside loss (lower partial moment of order 1). For commodities, the omega measure was 0.9217.

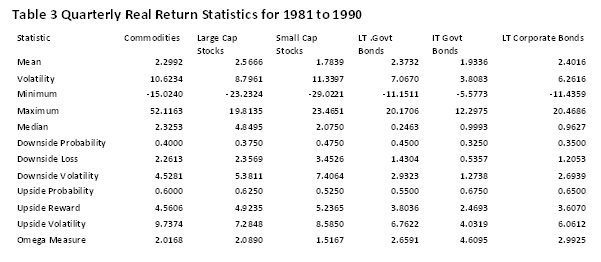

Tables 2 through 5 provide both traditional statistical moments, as well as the partial moments for six asset classes. The asset classes are commodities, large cap stocks, small cap stocks long term government bonds, intermediate term government bonds, and long term corporate bonds. Table 2 contains the statistics based on quarterly real returns for the time period 1971 to 1980. Table 3 contains the statistics for the time period 1981 to 1990, and so forth. In the periods of hyperinflation such as 1971 to 1980, commodities clearly provided superior risk adjusted performance as expressed by the omega measure. In the periods closer to the long run average, which for the forty year period was 4.41%, many other asset classes performed better than commodities. Stressful time periods such as 2001 to 2010 seem to make all investments have the same likelihood of having positive real returns. A portfolio of these investments might have led to better risk adjusted performance.

It is imprudent and dangerous for an investor to place all their capital in one asset class. We have discussed the benefits of diversification in a previous blog. The next blog looks at how a core exposure to commodities over long time periods may actually be beneficial to investors interested in protecting purchasing power.

Click To Enlarge

Table 1 Real Return Partial Moments Example

Sponsored by: EMA Softech

It is difficult to think beyond the crisis we have been facing as a deal is made in Congress to increase the debt ceiling. Conflicting economists predict either a recession worse than the one in 2008, or a continuation of sluggish economic growth. The baby boomers are faced with the problem of how to safeguard the assets they have, and somehow protect themselves from running out of money before their time.

This blog takes a look at how asset classes have fared over the forty year period 1971 to 2010 by using partial moments to quantify the likelihood that the purchasing power of these asset classes is protected and to what extent. It is helpful to see how annual inflation has changed over this time. Figures 1 to 4 show what happened. OPEC I and OPEC II occurred in 1974 and 1980. Investors at that time enjoyed double digit interest rates in their CD’s but also had to deal with double digit inflation. Since then, we have been enjoying inflation rates between 3% and 4%. In 2008, the inflation rate was just below zero.

Economists measure purchasing power by calculating the real return of investments. While we use the textbook formula for computing real returns, they are often approximated by subtracting the inflation rate for a given time period from the nominal or total returns of an investment. To protect purchasing power, the investor wants real returns that are greater than zero as often as possible (ideally all the time). If we apply the partial moment methodology, then the target return for real returns should be zero.

Table 1 illustrates how to evaluate the lower and upper partial moments for the real returns of commodities. They are represented by the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index using the quarterly returns and inflation rates over the time period 2006 to 2010. The downside loss was 6.0891% while the upside reward was 5.6120%. Con Keating and William Shadwick of The Finance Development Centre in London, developed a useful risk adjusted measure to rank investments in a partial moment context. They call it the “omega measure”, and it is defined as the ratio of upside reward (upper partial moment of order 1) to downside loss (lower partial moment of order 1). For commodities, the omega measure was 0.9217.

Tables 2 through 5 provide both traditional statistical moments, as well as the partial moments for six asset classes. The asset classes are commodities, large cap stocks, small cap stocks long term government bonds, intermediate term government bonds, and long term corporate bonds. Table 2 contains the statistics based on quarterly real returns for the time period 1971 to 1980. Table 3 contains the statistics for the time period 1981 to 1990, and so forth. In the periods of hyperinflation such as 1971 to 1980, commodities clearly provided superior risk adjusted performance as expressed by the omega measure. In the periods closer to the long run average, which for the forty year period was 4.41%, many other asset classes performed better than commodities. Stressful time periods such as 2001 to 2010 seem to make all investments have the same likelihood of having positive real returns. A portfolio of these investments might have led to better risk adjusted performance.

It is imprudent and dangerous for an investor to place all their capital in one asset class. We have discussed the benefits of diversification in a previous blog. The next blog looks at how a core exposure to commodities over long time periods may actually be beneficial to investors interested in protecting purchasing power.

Click To Enlarge

Table 1 Real Return Partial Moments Example

Sponsored by: EMA Softech

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)